The 1985 Project Part 36: Professor Longhair - Rock'N Roll Gumbo

An album from 1974 reached more ears in 1985

I was still young enough to try anything back in 1985, so when Tony Renner, then the editor of Jet Lag, asked me to go with him to see George Winston, I thought it might be something weird enough to do. Winston may be virtually forgotten now, but for a few years there in the 80s, he was a multi-million dollar machine. His solo piano noodling records put the Windham Hill label on the map and virtually created the New Age movement in music.

He hadn’t always been like that. His first album, in 1972, was released by John Fahey on his Takoma Records label, and it did something on piano akin to what Fahey was doing on guitar at the time. I did not know that until many years after I saw him live. I was flabbergasted, impressively so, to find that he made sure ushers provided all patrons at his concert with a pamphlet listing some 100 piano players with way more interesting things to say on the instrument than he was doing. I wish I could see that list again but I’m absolutely certain that one of those pianists was Professor Longhair.

Either shortly before or after I saw that concert, Winston reissued the album Rock’N Roll Gumbo on the label he had started as sort of a subsidiary of Windham Hill, Dancing Cat Records. Most albums on Dancing Cat were by Hawaiian slack key guitarists, so the Longhair record still stands out in the label’s catalogue.

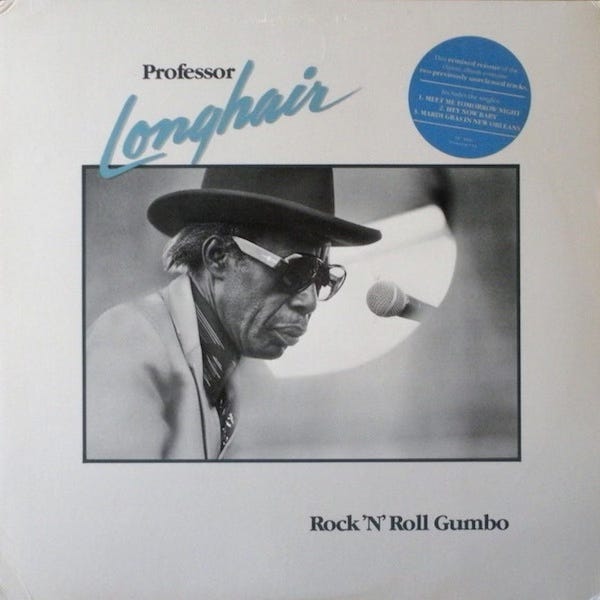

Rock’N Roll Gumbo had been recorded in 1974 and released in France and a few other European countries. It received a small reissue in the US in 1980. All of those issues have always been hard to find here in America. But with the clout of Winston behind it, the 1985 version of the album, with an entirely different cover, was heard by far more of Longhair’s fellow citizens.

Professor Longhair (real name Henry Roeland Byrd) is at the center of any history of New Orleans rhythm and blues. He had no real national hit records, but in that city where so many key developments in American music were born and or developed, the man known as Fess is revered. Almost every New Orleans piano player to come along after him – from Huey “Piano” Smith and Doctor John all the way to Jon Batiste – has had to master and incorporate the style of this man.

I knew a little of his music – certainly “Mardi Gras in New Orleans” and “Tipitina” – but wouldn’t really dig into it for another couple years after this album came out. I wish I’d taken Robert Christgau’s A- review to heart back then and nabbed it. It’s one of the better late period Longhair records I’ve heard.

Part of the reason for that is the presence in the studio of fellow Louisianian Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown. Brown was one of the most remarkable musicians of the 20th Century, a master of both guitar and violin, and capable of playing blues, jazz, country, or, as it turns out here, New Orleans r&b. The album is about 85% focused on Longhair, but Brown delivers some hot guitar solos on most of the songs. His fiddle playing on the version of “Jambalaya” here brings a further hint of Cajun music to the song Hank Williams always intended to be heard that way.

Song selection includes Longhair classics such as the aforementioned “Mardi Gras in New Orleans” and “Tipitina,” as well as a solo version of “They Call Me Professor Longhair.” Lots of other New Orleans faves, including “Junco Partner,” “Rockin’ Pneumonia and the Boogie Woogie Flu,” “Stag-O-Lee,” and “Rum and Coke” show off the ways Fess kept up with the music of those he influenced. There’s also a blistering instrumental take on Ray Charles’ “Mess Around” which fits the Longhair piano style perfectly.

That style combined elements of Caribbean rhythms such as rhumba and calypso with vague nods to stride piano traditions and the nascent style of rhythm and blues being born around the country in the late1940s when Longhair first recorded. It was highly infectious, highly danceable and containing all the rhythmic excitement one could need in the piano alone. The right hand glided across syncopated melodies which meshed with the rhythmic patterns of the left hand.

If I have a complaint at all about this record, it’s that the drums and congas put too many beats where they don’t need to be. The bass player does a terrific job of complementing Fess’s left hand, but the extra drum beats are sometimes jarring. It’s easy to forget about this problem, though, because the rest of the music is so good,

How have I gotten this far without mentioning Longhair’s singing? I love it to death and always have. He had a voice that moved between deep rumbles matching his left hand notes on the piano and higher squeals matching the right. He sang clearly and powerfully at all times. This was a man used to performing in small noisy clubs and he developed a voice that could capture attention in such circumstances as well as his piano could.

While I still prefer Longhair’s 40s and 50s singles, this record will more than suffice to scratch any itch to hear his music. I’ll give it 9 out of 10 points.